Conscious Consumption: I Shop, Therefore I Am

by Zinah Nur Sharif in Culture & Lifestyle on 31st January, 2019

The number of people within the Muslim communities loving fashion has visibly increased over the past decade. Modesty fashion is an ongoing movement that has been picked up online in the late 2008s. More young girls and women are using fashion as a means to demonstrate their Muslim identity. It’s something celebratory, having the freedom to express oneself through the means of fashion. What is concerning, however, is the increase of compulsive consumption.

The number of people within the Muslim communities loving fashion has visibly increased over the past decade. Modesty fashion is an ongoing movement that has been picked up online in the late 2008s. More young girls and women are using fashion as a means to demonstrate their Muslim identity. It’s something celebratory, having the freedom to express oneself through the means of fashion. What is concerning, however, is the increase of compulsive consumption.

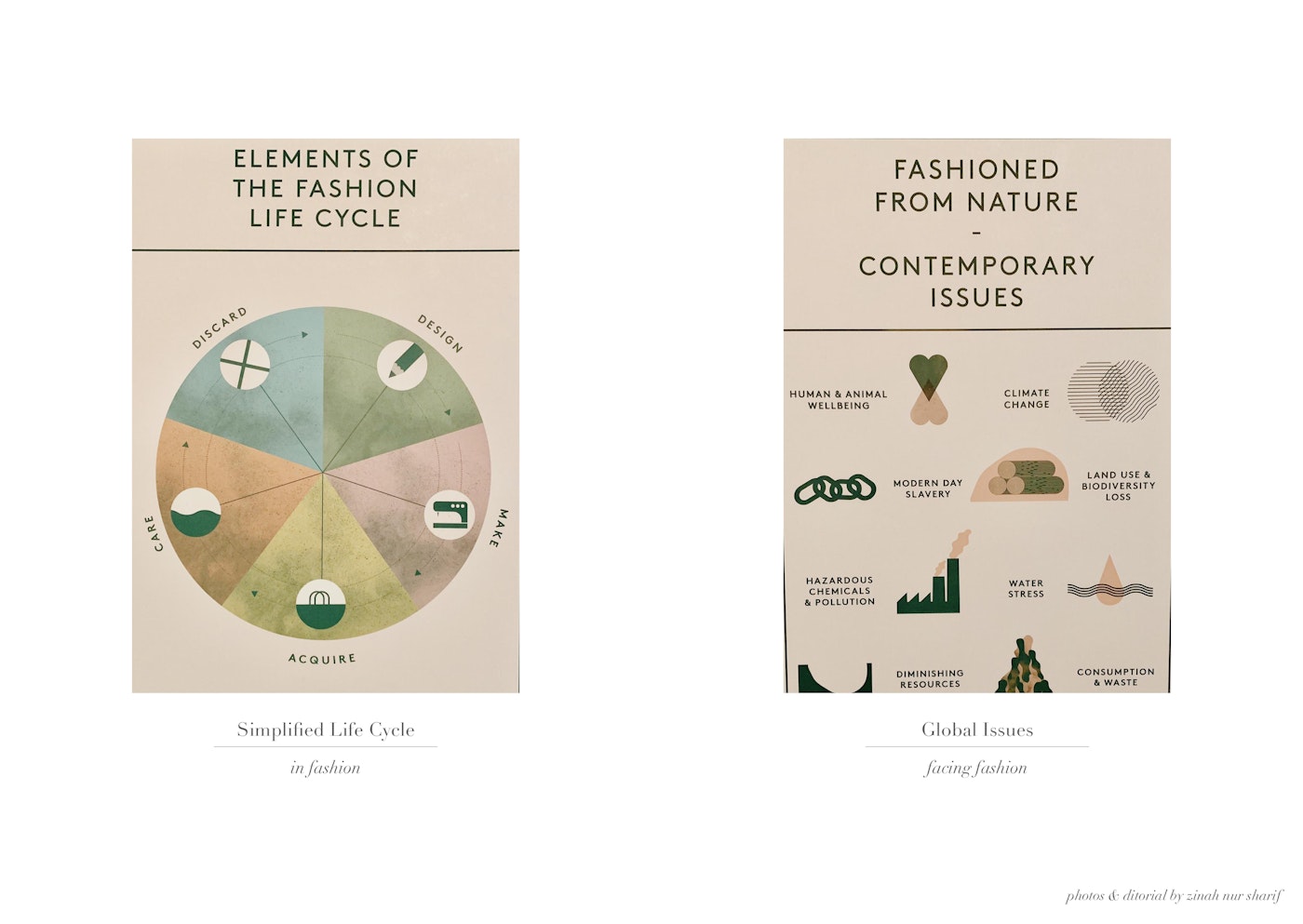

Loving fashion somehow comes with the automated denotation of shopping. More particularly, accessible fashion. This, of course, should not be the case, fashion is not synonyms of shopping. But fashion can be both style and trend; one emboldens consumption while the other acclaims to be timeless. It’s between prioritising quality or quantity and mindfulness or senselessness. What is perceptible is that more people are driven by trend and seem to reinvent their style through it, without consciously knowing the effects of consumptive buying has on our planet and fellow human beings. The unfortunate truth is that fashion is aiming to be infinite, but our planet and the people making our garments aren’t.

Let’s briefly look at the supply chain of fast fashion (or fashion in general), organisations start with sourcing the raw materials, not many are done so ethically or in a sustainable manner. The next step is usually finding the cheapest labour possible, setting aside basic regulations such as health & safety, labour hours, well-being or any form of the union protecting the rights of garment makers. Then it’s usually overproducing products (according to recent statistics, Inditex group produces 7 billion products consumed only by 1 billion of the world’s population)…we know what happens to the products that are not purchased? Landfills full of products that are toxic and harmful to its neighbouring citizens. These end up being in far Asian countries in remote villages, many of us unaware of their existences.

The gap and distance between the initial production steps and the final products are so vast, that majority of people don’t have an oversight of what is happening (that is also true to the agriculture and meat industry). However, with the digital world and more active organisations exposing and sharing every step of the industry, we really have no excuse to oblivion. But then, the question of finance comes into place, the intention of high street fashion was to make fashion accessible to everyone, regardless of social class and income. One should be able to buy a stylish pair of shoes at £20 instead of breaking the bank at an artesian shoemaker. However, how many pair of those £20 shoes does one need? Is it worth the suffering of the planet and others for one to have that pair of shoes? Has anyone watched ‘The True Cost’ and saw the scene where a garment maker is begging the audience to stop buying products made out of their blood, tears and sufferings? Garment workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia and India have no choice of quitting the job if the work hours exceed 20, or the work environment causes them potential terminal illnesses (or even death, as the events of Rana Plaza showed) or have the privilege to find another job. Working there is survival, to feed oneself and take care of a family. It’s not the kind of poverty where being on government benefit is a back-up plan.

We as a Muslim community really have to build a conscious of everything we consume, the effect it had or has on the planet and our fellow human beings (and animals!). Thanks to organisations such as Eco Age and Fashion Revolution, big corporates are being held more responsible and regulations are being put into places to protect everyone involved in the industry, especially the garment workers. We encourage you to read and expand your knowledge on them. It allows everyone to make the right decisions of where to purchase and how often. Priorities quality over quantity, identify your personal style and stick with it. Invest in pieces that are ethical (perhaps more expensive) but have longevity. It certainly isn’t an easy task, but it’s something to be conscious of. Wearing clothes for modesty is a necessity, fashion is a luxury (yes all fashion, even those ‘trendy’ high street bargains). How one shops is a reflection of their identity, lifestyle, and mindset. Perhaps, some of us can’t comprehend that modesty is not limited to appearance, but how we are, who we are and how we treat everyone and everything around us.

Zinah Nur Sharif

I’m currently a PhD candidate at the University of the Arts London, undertaking a research about the symbolism of the headscarf & intersectional identities of Muslim women. I live between Hong Kong and London, love to travel, the arts, fashion and culture. I had the privilege of living in 6 different countries over the past two decades, which has allowed me to naturally intertwine respectively unique cultures to form my own distinctive creative identity. My work focuses on creativity, communication, and visual storytelling. I specialise in marketing communication and luxury fashion sector. To learn more about my project, you can visit my Instagram: @zinahns and website www.zinahns.com