Why Muslims Need to Archive Their History

by Selina Bakkar in Culture & Lifestyle on 19th October, 2021

Everyday Muslim Heritage and Archive Initiative (EMHAI) was established in 2013 to create an archive collection to document and preserve the UK’s lived Muslim experiences. Sadiya Ahmed founded the initiative to address the noticeable absence of the historical and contemporary Muslim narrative from the archives, museums and history books of Britain. An intrinsic aim of the initiative is to place Muslim history and heritage directly within the context of broader British history.

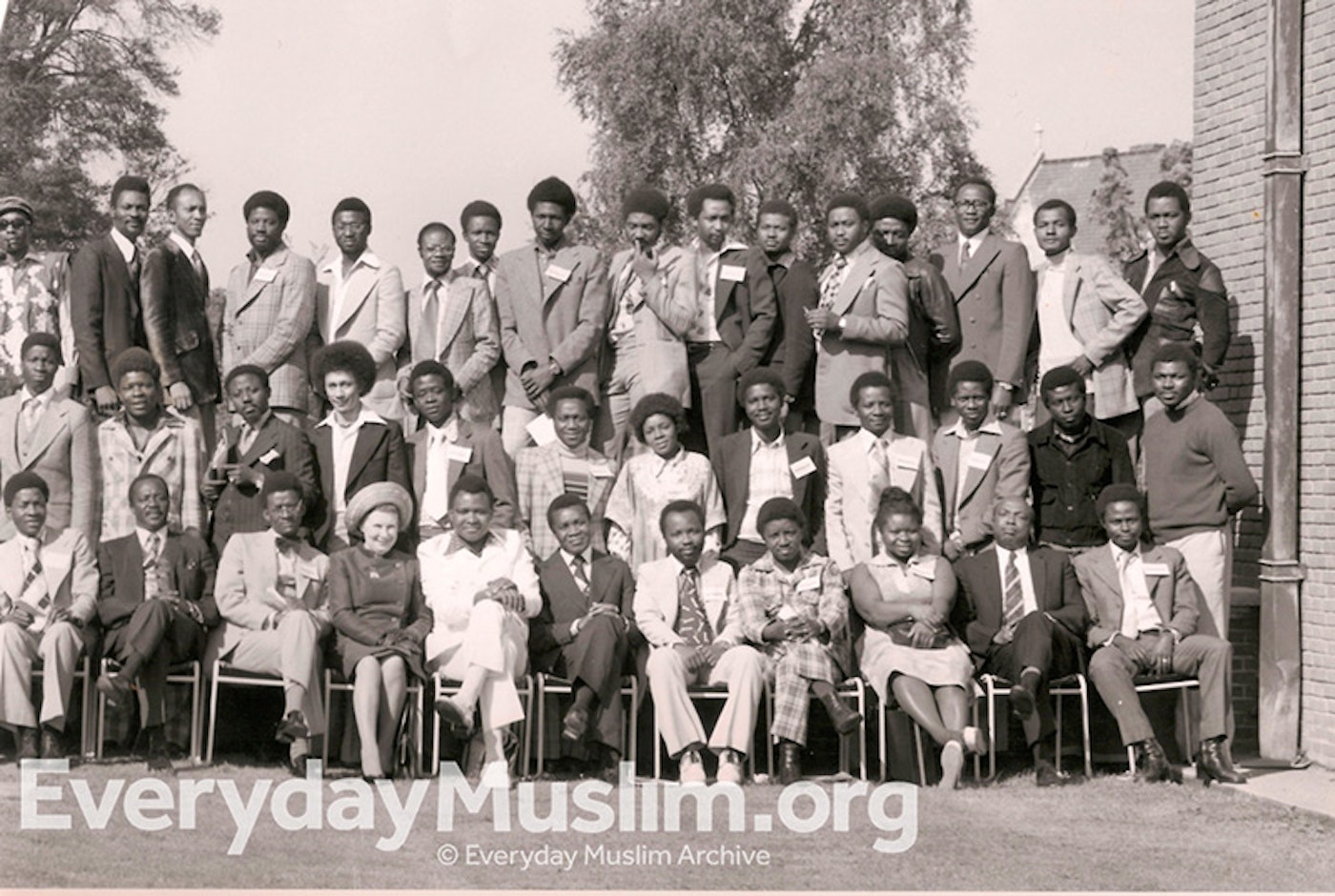

The EMHAI archive collection is an ever-expanding collection of video and audio recordings and oral history interviews from Muslims of diverse ethnic backgrounds across the UK. These are included alongside a wide-ranging depository of approximately 2000 digitised documents and photographs that provide both a historical and contemporary narrative of the everyday lives and diversity of the Muslim communities living in Britain. The collections are available online, partially catalogued and archived at archival institutions across the UK, including Bishopsgate Institute, Vestry House Museum, George Padmore Institute, Surrey History Centre, Brent Museums and Archives. An intrinsic aim of the initiative is to place Muslim history and heritage directly within the context of broader British history.

At the moment there are three archive collections: the first is ‘We Weren’t Expecting to Stay,’ a collection of South Asian experiences in London 1950 -2010, the second is ‘Exploring the Diversity of Black British Heritage in London’, the first archive collection based on the stories and memories of the Black, African and Afro – Caribbean (BAAC) Muslim community in London, and finally, ‘Archiving the Heritage of Britain’s First Purpose-Built Mosque’ which documents the history of the Shah Jahan Mosque and Muslim life in Woking through the stories of Muslims dating from the 1880s to the present day.

In developing each project, we make sure that an advisory board consisting of academics, community members and heritage professionals are represented. It has always been an endeavour to produce collections that can be of historical value in academic and family research, be preserved to the highest archival standards, and provide the community a space in which they can take ownership of the telling of their experiences and how they are represented in history.

QUESTIONS:

- Let’s start with the basics: Can you explain what archiving means for the average person?

For you and me, archiving starts at home. A family archive can include anything from the family album, recipes, a passport, diary or a journal, a vase, clothing…literally, anything that has a story, be it personal, cultural or of historical significance. Usually, these are everyday objects which we have no reason to view as historically valuable. Yet, we seem to appreciate them as such when they represent another community’s history. I feel this is mostly because we do not see ourselves represented in heritage spaces such as museums and archives. When we are, it is usually from a colonial perspective and not from an authentic or indigenous curatorial consideration.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by EverydayMuslim HeritageArchive (@everydaymuslimheritage)

A more conventional explanation of what an archive is that it is a collection usually consisting of documents or records that provide information about a place, institution, person or group of people. These can include letters, photographs, film or audio recordings, minutes of meetings, publications, leaflets, newsletters and many other examples relevant to a family or an organisation. Over time these records can become of historical significance.

These collections preserve the heritage, culture and experiences of a community from a social, political and personal perspective. For me, I see an archive collection as a form of storytelling but with the added value of attaining historical significance over time that can be accessed for research by academics, historians or members of the public.

2.Why is archiving important?

Archiving allows us to use official channels of documenting and preserving history in a way that provides our testimonies of our existence and experiences a legacy that will precede us. We can do this by placing collections in local archive institutions. We can also implement accredited preservation and recognition methods through ensuring grading and listing of buildings, and initiating a blue plaque status for people and places significant to Muslim history in Britain.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by EverydayMuslim HeritageArchive (@everydaymuslimheritage)

Through Everyday Muslim, I want to:

- Address the absence of Muslims in British history and place alongside the already archived broader British history in archives, museums and academia.

- Educate and empower the Muslim community in creating tangible connections between their Muslim heritage and the representation of their identity in the wider society.

- Advocate a sense of belonging to subsequent British-born and immigrant Muslim generations.

- Engage with a large and diverse audience to promote understanding, awareness and learning about the everyday aspects of Muslims’ lives.

- Identify, document and celebrate the contribution of Muslims in society today and in a historical context.

- Encourage engagement with museums and archive collections.

- Why should we as British Muslims care about archiving our history?

There are many theories, many examples, many quotes and ways of explaining the importance of archiving but, something that really resonated with me was a quote by George Orwell; “The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.” I find this quote so relevant to the Muslim community in Britain because as we try and hold on to the fragments of our parents’ indigenous history to form a part of our own identities there is still a feeling of incompleteness because we are so disconnected from our history in Britain. No matter how contemporary it may be, the history of a place in which we live provides us with a sense of belonging which we don’t feel unless there is a connection. This can be with people, places, events or buildings. Collectively or individually, fragments of this history are passed through our lives to subsequent generations. Without it as a foundation, each generation starts out as the first.

Without knowledge of what has happened before we have to start from the beginning and consequently the progression of our communities is slower as we tend to get caught up in the glory of being ‘the first’ rather than questioning why after several generations we are celebrating firsts and not more established in every aspect of society.

The quote also makes me think about how archives are integral to documenting and preserving our stories, our identities, who we are, where we came from, our language, our community, and if we don’t fight to save it, no-one else will. Like the erasure of thousands of years of Muslim presence in Britain, our stories too will be erased.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by EverydayMuslim HeritageArchive (@everydaymuslimheritage)

This point has become glaringly more evident in recent times, especially in relation to how history is taught in our classrooms and the uncovering of histories that have been suppressed. One obvious example would be the fairly recent discovery that collectively, over one million Muslims fought for the British army in both world wars, a fact that most of us who learnt about the wars throughout our schooling in Britain were completely unaware of any retrospect, it brings new meaning to the taunt ‘My grandfather fought for you to be here!’ something you would have only ever heard from someone from a white British heritage.

It’s quite easy to bring meaning to the process of archiving to minority communities by using words like ‘representation,’ ‘authenticity’ and ‘legacy’ but, behind the buzzwords is the reality that taking ownership of ‘writing one’s own history’ is actually creating a foundation from which our ethnically diverse communities are able to reflect on, grow and learn about each other from and most importantly, this foundation creates a sense of grounding, a sense of belonging, and a level of equity in the ownership of a place in the sense of it becoming ‘home.’ This is something that without a history becomes more difficult to establish, and what I mean by this is that we are always seen as immigrants.

Regardless of how many generations have resided here, there is always a sense of othering.

- What communities are well represented in the archiving spaces?

Mostly those who are from the indigenous white upper-classes, royalty, and aristocracy. Although in more recent times, contemporary collections around social movements, homelessness and other minority groups have started to gain popularity in both collecting and documenting spaces, and also for research purposes.

- Which communities need more archives?

Minority communities are generally more absent from the archives, of which the Muslim community, because of its faith and its rich diversity, is more absent than others.

And what tips would you give to someone considering archiving?

- Don’t overthink it.

- Question why something would be valuable in the future.

- Look after it as best as possible.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by EverydayMuslim HeritageArchive (@everydaymuslimheritage)

6. What should we be archiving? Can you give us some examples, maybe formats eg oral, visual etc.

We should be archiving conversations, photographs, certificates, diaries, recipes, ornaments, clothes. What can be archived is actually limitless but, start with what is important to you, your family, organisation, or your story. You don’t have to ‘give away’ or relinquish your items or ownership of them, but start to record audio or video interviews, scan photographs and documents to create digital archives. We can now create digital archives using smartphones but for them to be of archival standard, they have to be preserved to the highest digital standard. Audio recordings need to be recorded and saved in WAV format, video recordings should be recorded in the highest quality to which you have access, depending on your recording device. Whilst scans of photographs should be of archival quality (i.e. must scanned at least at 600dpi), this can be achieved on most scanners. And ALWAYS make a back-up copy and keep safe at a different address.

- How does movement/displacement affect archiving? Is there less available to archive as people leave behind belongings and places?

View this post on InstagramA post shared by EverydayMuslim HeritageArchive (@everydaymuslimheritage)

There are two ways of answering this question. The first is to say that movement and displacement usually but not always is initiated through a need of ‘having to move’ and when that is coupled with leaving family or a war situation then belongings are few and far between. So, it can be said that archiving becomes difficult as either belongings and places are left, behind, lost or destroyed. However, I feel that even in those situations, all is not lost. We have our memories, stories and experiences that provide an invaluable insight to a living memory of those places and personal experiences that always enhance the more traditional forms of archiving.

- What book would you recommended for anyone new to archiving?

A good place to start is: A Guide to Preserving the History and Heritage of Muslims in Britain: Mosques, Madrasahs and Islmic Supplementary schools which actually can easily be used as a guide to creating a family or any type of organisational archive. It has basic tips and easy-to-understand language.

- How did you get into archiving and why?

It all started with a trip to the Roald Dahl Museum I think in October 2009. It was the year it was voted Museum of the Year. Growing up with Roald Dahl books as a child, my own children were beginning to read them, so the trip was a chance to share in the books’ fun and fantasy and encourage them to read more. The museum experience didn’t live up to my expectations, and on the way back home, I felt underwhelmed and that we had a wasted journey. But then I heard my daughter talking excitedly about what they had seen and from their conversation, I realised I had been wrong. They had learnt so much. I felt that because they had the opportunity to explore by themselves, they could learn and discover in their own way. My children were relatively young at the time, and I found it difficult to find somewhere they could learn about Islam and read Qur’an other than the traditional madrassah (Islamic school) environment. The museum trip gave me the idea of thinking of learning in a more self-directed ‘outside of the classroom approach.

The initial project’s idea started off as a Muslim heritage museum that would include sections for art/literature, Islamic History, Scientific and Other Global Contributions, and Muslims’ History in Britain. It’s working title was ‘Verity.’

However, the motivation ‘to do something’ was always there. It came from the convergence of my parents’ stories from my childhood of their lives growing up in Pakistan and Kenya, their early lives, and experience of making a home in Britain. Also, from growing-up in an inter-generational household of siblings; some of whom are around fifteen to twenty years younger than me and the intertwining of four generations’ experiences, including that of my children’s. It made me realise that we are all but transient guardians of our history. One of the project’s founding reasons is to build intergenerational connections to better understand the past and encourage future generations to make informed decisions by understanding the previous generations’ experiences, cultural pressures, and broader socio/economic climate.

- Did growing up as a Muslim person of colour in Britain affect your approach to the archive?

Growing up as a person of colour and a Muslim in Britain has been challenging for many reasons, and for all generations, in different ways. Like with any community, there are always generational differences. Yet, with a diasporic community, these differences can be further amplified by adding cultural and social nuances between personal heritage experiences and living in a society that sees itself at odds with anything that is not part of their culture. When such differences began to be questioned by my younger siblings, I began to notice that I understood my parent’s generation in terms of their actions and decisions more than my younger siblings and their peers. Even if I disagreed with their choices, I understood their reasons. It became apparent to me that I was aware of my parents’ personal experiences, and had a little insight into that time’s social and political climate.

Just fifty or sixty years ago, the ‘Muslim’ community we refer to was in its infancy. Many people came alone or as a couple. Without their extended families, there were no mosques but instead, gatherings in designated houses. They also had little to no halal meat shops, or access to spices and other ingredients. Many faced very open racism both in society and institutionally, which I too experienced growing up. They also faced isolation, as communication was not as instantaneous as it is now. Back then, to communicate with their family, they had to write a letter that could take two weeks to reach its destination and another two before receiving a reply. Or ‘book’ a phone call through an operator which was both expensive and limited to just a few minutes. Often the connection was wrought with interference and usually ended without much of a conversation. At the time, most people didn’t even have a phone in their homes, let alone in their pocket as we do.

It made me appreciate how we can take everyday decisions or actions for granted, such as buying halal meat, calling each other for a chat or advice, living with or near family, celebrating Eid together or praying in a mosque.

It also made me realise that if such experiences are unknown, then there is a disconnect between generations that results in a loss of connection to their culture and heritage, thereby contributing to a lack of empathy and knowledge of how a community endeavours to establish itself and the rationale behind past decisions and actions. Most importantly, it marginalises the perspective of those involved; Whereas I felt having known and experienced some of the ‘past’ using my view, I was able to help to shift attitudes and allow a space for understanding and healing. The stories became a unique insight into the past, understanding their influence on the living present. At this point, I realised that before establishing a museum or ‘museum-style’ physical learning space, I needed to think more long-term of something more tangible, something that would have historical significance.

A chance meeting with Michelle Johansen from the Bishopsgate Institute led me to understand the significance of archives. The meeting led to our first archiving project; ‘We Weren’t Expecting to Stay’. When I began the project, I didn’t even know that the words history and heritage meant two different things and would use them interchangeably – archives could have been a foreign word for all I knew!

But I did know that the archives were the place to start. These are what a legacy is built on, and these are what our community was missing. I soon realised that the archives are our legacy. Archiving our family and community history enables us to connect the dots and points of reference, for subsequent generations to build upon.

- Do you think that the arrival and rise of tech has made archiving easier or more difficult?

We are seeing many ‘archiving’ projects on social media which are wonderful as they are really making the idea of archiving accessible and raising awareness of its importance to our communities. However, many of these projects are not being archived beyond the internet. They are also not being archived to archival standard, which means they are not always accessible, and it is not clear where they are being archived and if they are, or will be publicly available. So any organisations undertaking archiving as part of their projects should seek guidance on how to archive. It may add to their workload, but archiving these conversations, events and other multi-media is an essential act of preserving our voices and will act as an equaliser against the anti-Muslim rhetoric and bias of the media which will inevitably be preserved in prosperity.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by EverydayMuslim HeritageArchive (@everydaymuslimheritage)

- Which buildings, projects or institutions run by Muslims are you currently exploring for your archival work?

View this post on InstagramA post shared by EverydayMuslim HeritageArchive (@everydaymuslimheritage)

Other than family archives, those of organisations such as community supplementary schools, mosques, small businesses, ISOCs, charities, clubs and societies are extremely invaluable in terms of representing the establishment of communities, their needs and of the support and services they provide. And, not to mention how they change throughout the generations. The potential archives to be collected here can include, promotional leaflets, prayer timetables, letters, minutes of meetings, photographs of buildings or events. As a collection, these materials are evidence of a journey and experience that is/was integral to a wider society. And that is something that is really imperative to stress. We and our histories are not lived in exclusion to that of the indigenous society. In the past fifty or sixty years, our community’s presence has changed and enriched the cultural landscape in the UK through cultural influences of food and clothing and is expanding all of our education through providing alternative viewpoints on society, politics and history.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by EverydayMuslim HeritageArchive (@everydaymuslimheritage)

- Once you decide to archive, do you just give it to a family member or is there somewhere to send this information?

Archiving can start and, if preferred, stay within the family. There is much we can learn from our own family history in terms of forming personal identities, sharing and fusing cultural legacies through food, clothing or language. It is a deeply personal way of connecting ourselves and our family to a culture which may be physically distant but is present within our surroundings and our people. However, making archives publicly available helps not only build a whole community identity, but it also conversely helps to reflect our diversity in culture and language which seems to be oppressed by race and ethnic groupings in the UK. Public archives support our communities by providing an authentic legacy in a historical context which has traditionally been erased simply by its exclusion. Creating our own archives gives us control of our narrative and the power to counteract the dominant hostile and condemnatory narrative of Muslims in the media and history books.

- What is an example of an interesting story you found through your archiving work?

It is impossible to choose one story as every interview we have conducted has shed a new light on places and experiences of a Muslim living in Britain in a way that cannot be quantified here individually. However, collectively these archives and our stories place Muslims firmly within the context of wider British society and its history in a way which provides evidence and testimony that provide a collective legacy but also serve to demonstrate the complexities and divergence of Muslims in Britain.

Selina Bakkar

I'm a simply striving to be better and improve in different areas of my life through more self awareness, experiences and learning more about the deen. You'll find me talking about community, connection, planting & growing, seeking the truth in an age of propaganda and misinformation. This year I want to document more to do with food heritage and history so watch this space or reach out. Have a listen to the Amaliah Voices podcast where I talk passionately about Islam, nature, motherhooding and back home. Link in bio peeps. To join the Amaliah Writer Community email me at selina@amaliah.com IG: SelinaBakkar