Is It My Responsibility to Represent 1.9 Billion Muslims in My Writing?

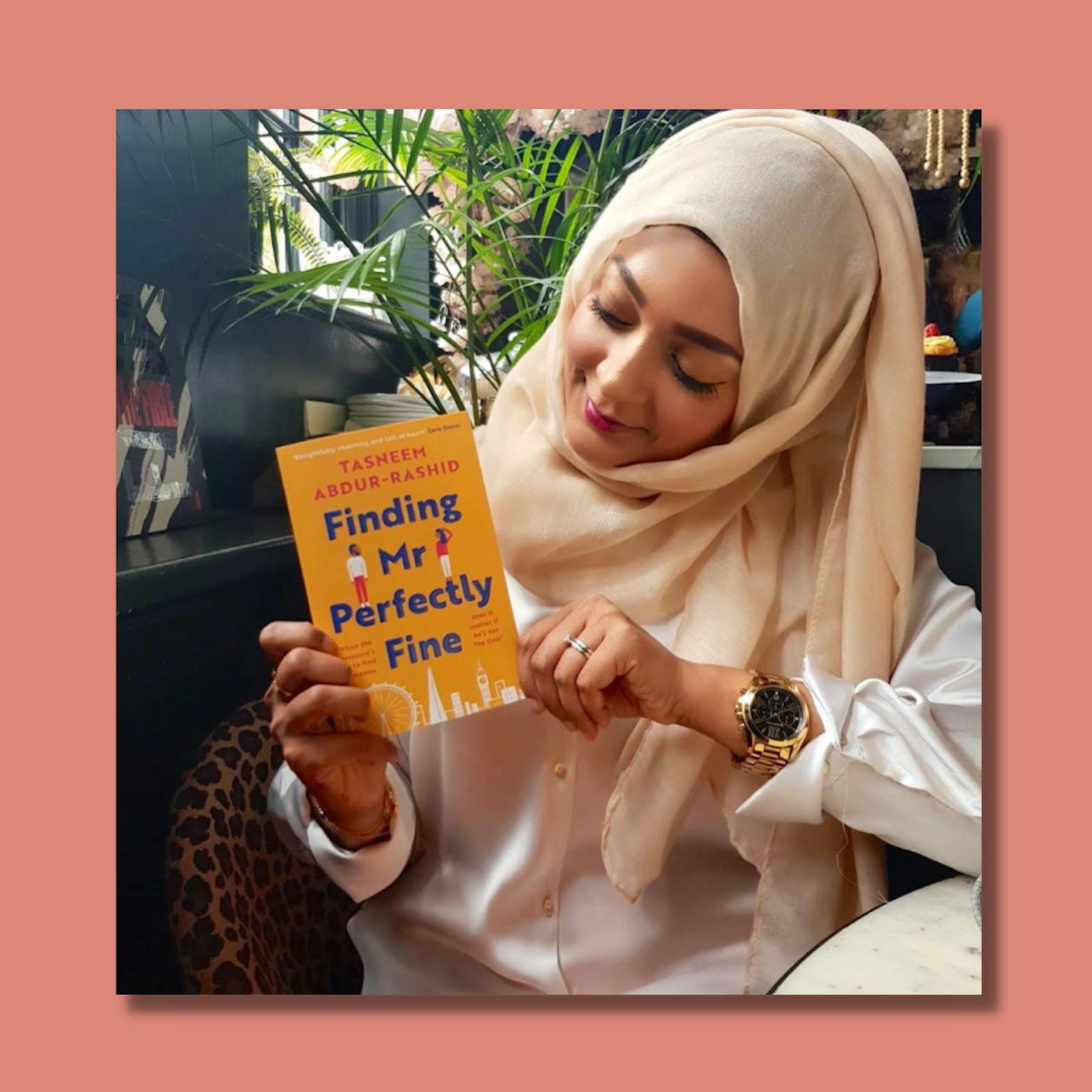

by Tasneem Abdur-Rashid in Culture & Lifestyle on 17th August, 2022

Debut novelist Tasneem Abdur-Rashid explores the pressures, expectations and challenges of writing as a conscious Muslim for a diverse audience, and how Muslims can navigate these challenges with authenticity and sensitivity. With Muslim representation in books increasing she explores the responsibility and role of authors.

I first started writing my book, Finding Mr Perfectly Fine, for a Muslim audience. Having grown up in the UK where the publishing industry lacks diversity, I didn’t think anyone who wasn’t Muslim, or at the very least, Asian, would be interested in a story about a Bengali girl from London looking for a husband. I posted chapters on a blog that my friends would read, and writing for my own people felt liberating. Not having to worry about the white gaze and not having to write in the same way I live my life – painfully aware of the fact that the scarf on my head makes most people think I’m a spokesperson for Islam – would be a relief, like the exhalation of a breath I had been holding my entire life.

And at first, it was. But during the process of looking for an agent and publisher, I realised that my book couldn’t be entirely for Muslims. Yes, they were my core audience, but I had to consider the fact that non-Muslims would read it too. With a fraction of the UK population being Muslims, and with publishers looking for books that would sell, it had to appeal to a bigger audience.

I went from writing for my people, to writing for those who had no idea what life was like for someone like me, and slowly, the liberation morphed into shackles. I was no longer merely telling a story, I was ‘representing’, and the responsibility felt overwhelming.

I don’t need to explain the way Muslims are portrayed in the media and arts. It’s only very recently that we have had Muslim characters that aren’t victims or terrorists, and are well-rounded humans with desires, goals, ambitions. But the years and years of negative narratives has resulted in deep-rooted, dangerous stereotypes about us. Our women are oppressed/abused, our men are misogynistic/violent, we’re all miserable/angry victims desperate for white salvation/justice.

As a visible Muslim, 9/11 turned me into the face of Islam, the Iraq War and Middle Eastern politics. I was a teenager in London, listening to Britney, Aaliyah and Eminem. I knew nothing about the war or Middle Eastern politics. But overnight, I became both a spokesperson and threat, and I’ve been bearing that burden ever since.

A couple of decades later, I began writing a book about Bengalis in London and every word I typed felt loaded. I had an agent, and a publishing deal, and I was no longer writing for myself or the handful of people who would read my blog. I was writing for a bigger audience and I had been conditioned to believe that it was my job to portray Islam and Muslims in the best light.

On the other side of the double-edged sword, social media had shown me what happened to visibly Muslim women when they fell short of the expectations from fellow Muslims. Even Nadiya Hussain, the nation’s sweetheart, wasn’t immune to Muslim and Bengali trolls. If she wasn’t spared, then who was I to get away with writing whatever I wanted without consequence? I was terrified of writing something that would be seen as portraying Islam/Muslim/Bengalis negatively, I was terrified of fuelling stereotypes. I had no idea how to create characters, and a story, that was authentic yet positive.

Did this mean that none of my characters could make mistake or do bad things, because they were Muslim?

Unfortunately I didn’t think to talk through my doubts and concerns with fellow writers until after my book was published. And when I eventually reached out to my peers, I was relieved – but also saddened – to find that I wasn’t the only one who had these concerns or experienced similar internal conflicts.

I turned to other writers to hear their thoughts.

Yousra Imran

Yousra Imran, author of the Young Adult novel Hijab and Red Lipstick, says, “The burden of representation as a Muslim author is very heavy. I don’t think any other author from another faith group feels the burden or is held to account the way we are. And of course, it’s absolutely got to do with the level of hate Muslims receive in the media. We feel conscious about not adding to it.”

Sabba Khan

Architect, writer and graphic artist, Sabba Khan, also felt this pressure when writing her award-winning graphic novel The Roles We Play. She says, “I was VERY aware of my Muslim community and family. I was living five doors away from the house I grew up in during the bulk of the writing/drawing of my book. I didn’t want to upset or do anything that would be considered slanderous – I wanted to be respectful – but at the same time I knew I needed to honour to my own experiences too.”

Dr Khadijah Elshayyal

On why Muslims feel the need to positively represent, Dr Khadijah Elshayyal, Associate Fellow at Edinburgh University’s Alwaleed Centre specialising in British Muslim identity politics and representation, says, “Muslims often feel this kind of responsibility, subconsciously even, and it frames or influences our narratives and thought processes. Part of this is because societally and structurally we are often called upon to ‘explain ourselves’. If in literature or other creative spaces, Islam and Muslims/Muslim cultures tend to be otherised or minoritised, or presented as exotic, unusual, awkward, quaint or primitive, then Muslims speaking in those spaces will understandably want to go against the grain. The weight of such one-dimensional/flat and persistently negative characterisation may then give rise to an impulse to counteract with exclusively upbeat positivity.”

So is it our responsibility, as Muslim writers and creatives, to try and positively represent 1.6 billion Muslims in our work?

Shaheen Kasmani

According to artist Shaheen Kasmani, the responsibility is not on our shoulders. “Like with any community that has been consistently marginalised and demonised, this responsibility has been imposed upon us. That we are constantly in reaction to them, is an internalisation of that narrative, that it is something to be constantly proved wrong, to be shouted about, in addition to just getting on with our lives.”

While the overwhelming consensus is that it is not our responsibility to bear – regardless of how we may feel – there are ways in which we can write authentically and sensitively.

“I think we can only try to do our best to represent Muslims positively but without jeopardising the authenticity of the book or its storyline – if it doesn’t make sense to the storyline then the story won’t be believable,” Imran explains. “I think what’s more important is that we have a wide range of stories out there – both the positive and the uncomfortable. I do believe we are slowly getting there.”

Dr Elshayyal says that one way to navigate this challenge is to intentionally consider who your audience is. “Who are you writing for? Who are you addressing or in conversation with? In what sorts of spaces would you like to see your writing received? We all have issues that we want to foreground in our writing, drawing on our experiences perhaps or our worlds more generally… but being mindful and intentional of who we are addressing can be freeing because you can consciously and deliberately let go of the burden of ‘changing minds’ or ‘clarifying’ or dispelling prejudice – this idea of representing to an external gaze can be overbearing and can chip away at our authenticity. Being intentional about writing (or producing) for audiences of good faith (not necessarily Muslims) gives some freedom to address difficult/negative/complex issues without worrying about how it will ‘look’.”

Similarly, Kasmani says, “I think it’s important to tell your story, whatever that story is. But it’s also vitally important to contextualise that story somehow – what’s the framing, what’s the bigger picture, and through whose gaze are we viewing/watching/reading?”

I wish I had sought this advice from my fellow sisters in creative spaces before I wrote Finding Mr Perfectly Fine. It’s too late for me to go back and write completely authentically. It was always my intention to write so that people who looked like me could finally see themselves in mainstream literature. However, the burden I felt, stopped me from writing a book with a hijab-wearing protagonist as I was worried that if she made mistakes or did anything un-Islamic, I would be crucified by fellow Muslims and hijabis. Being hyper-aware of non-Muslims readers, also stunted my story.

Dr Elshayyal says, “The persistence of negativity and combinations of (sometimes latent, sometimes overt) prejudice as well as laziness/inaccuracy in depictions of Muslims can narrow and constrain possibilities, options and even the imaginations of Muslim authors themselves who have to operate in such persistently difficult and even hostile environments.”

The ironic thing is, despite being incredibly careful and mindful of how I portrayed Islam, I still received criticism from some Muslim women about my depiction of hijab, or the fact that my protagonist wasn’t very practising. As a hijab wearer for over twenty years, this came as a shock to me. But it also taught me a valuable lesson: try as we may, we can never please everyone – and nor should we attempt to. All we can do is write from a place of love, with good intentions and with respect, and leave the rest in Allah SWT’s hands.

Tasneem Abdur-Rashid

Tasneem Abdur-Rashid is a British Bengali writer born and raised in London. A mother of two, Tasneem has worked across media, PR and communications both in the UK and in the UAE. Today, Tasneem spends her days writing novels and her nights co-hosting the award-winning podcast Not Another Mum Pod – and in between, she’s busy trying (and often failing) to be super mum, super wife and super chef. Having recently completed a Master’s in Creative Writing with distinction, Tasneem’s debut rom-com Finding Mr Perfectly Fine was published by Zaffre/Bonnier in July 2022. You can find Tasneem on Instagram: @tasneemarashid and @notanothermumpod