I was first introduced to the notion of al-’ahd, the covenant, a decade ago during a course on Quranic Translation. Our professor was a brilliant Egyptian Scholar whose translation is by far the most accessible. Throughout the course, I was struck by the recurring use of ‘Afa la tatadhakkarun “افلا تتذكرون” which was often translated as “Do you not take heed?” and “Will you not be mindful?” in the context of the ayah. I wondered what the basic translation of the verb “tatadhakkarun” to “Do you not remember?” entailed and whether it referred to remembering innate ideas and truths we knew before coming into the world. Once I learned of our covenant, al-‘ahd العَهْد and that the timeline of Islam has started before humans were breathed into this world, it started to make sense.

I learned that it started with the divine question “Am I not your lord? “ألست بربكم to which we were witnesses and we testified in reply: “Yes my Lord. بلى قالوا ”. This is further evidenced by the Quran’s questioning on multiple occasions “ألا تتذكرون’ Don’t you remember?”

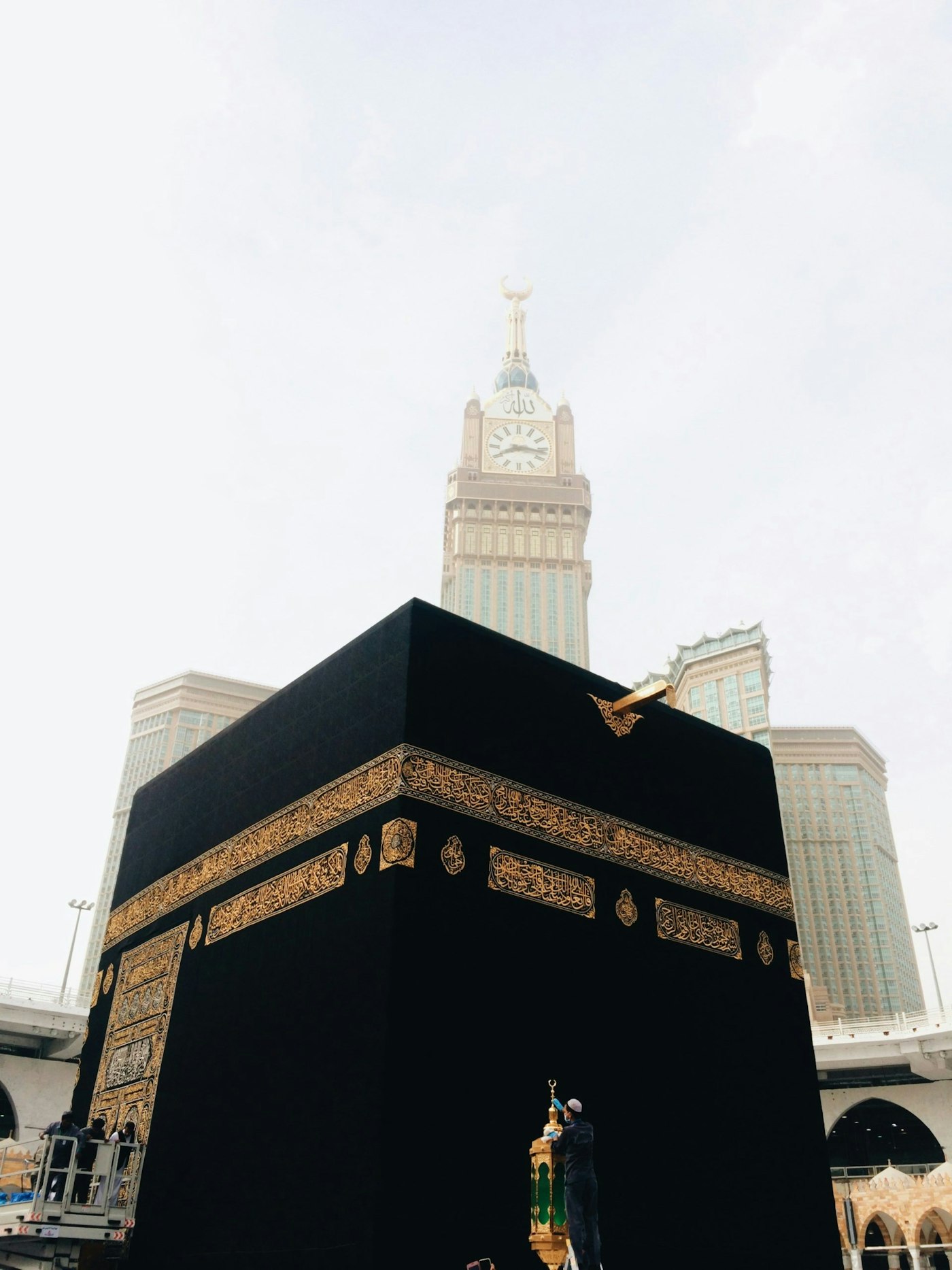

I understood this through the reliable gears that animated my logic but had not internalised it in my soul until I visited the Kaaba when I went to perform Umrah. Upon seeing it for the first time and being in awe of its Majesty conferred by Allah, a wave of familiarity and wonder swept over me, it was clear I was remembering the primordial covenant, a vocabulary we once spoke fluently but is now veiled.

With many of us having returned from performing Umrah, maybe seeing the Kaaba for the first time, in Ramadan and having spent a month in worship of Allah (SWT), fulfilling our covenant to Him, it presents an opportunity to ponder what this really means for us.

Here are 6 ways performing Umrah helped me to “remember” my covenant with Allah (SWT)

1. Remembering our unbroken lineage making up our Ummah

During Umrah and Hajj, pilgrims wear two unstitched pieces of white cloth, devoid of any signs of modernity. These are the same clothes that pilgrims have been wearing for hundreds of years and upon seeing this, we can feel an unbroken lineage starting with Prophet Muhammad (ﷺ) and our Muslim ancestors until today. There is authority in tradition, not the kind that some misuse, but that which is articulated in Sanad – the unbroken chain of authority of hadith, that props us up when our iman falters and we fall back.

It is the hands of our ancestors on our shoulders, and their ancestors on their shoulders, forming a tight fabric that protects and keeps us together as an Ummah.

The might of the Ummah was never clearer to me than at that moment. After living alone in Europe for many years, and upon seeing the sheer volumes of pilgrims coming from all over the world for the sake of Allah (SWT)’s pleasure, I cried out in naïve exclamation to my mother, “SO MANY MUSLIMS!” Her reaction was a mixture of amusement and clear reconsideration of the level of my intellect, and rightly so. There is a certain comfort in being among Muslims, to have a safe space, as it were, where our collective intentions and actions align.

2. Remembering that our existence revolves around the Divine

The first prayer in the basin of the Kaaba is a special one. Prior to that first Raka’a, our Qibla, as quintessential as it is, remained an abstract concept. Five times a day we face the Kaaba from all four corners of the world. We look for a needle on an app pointing towards it and imagine a space in our rooms, our offices, our mosques that aligns with that orientation. We internalise these coordinates with our bodies and our hearts, seeking it daily in prayer and remembrance. But nothing could’ve prepared me for the overwhelming feeling when I finally saw the Kaaba in person. Upon finally standing in front of it, an overwhelming feeling of belonging and homecoming swept over me. I was filled with longing, and eventually, exuberance at finally meeting in person a friend I held so dear. Later I realised that what I was feeling is not just my personal experience, but a truth shared by everything in existence. Ustadh Mustafa Briggs reminds us that we are part of a cosmic tawaf by the entirety of creation praising Allah,

“Planets are floating in their own orbits, the moon is doing tawaf of the earth, earth around sun and [within ourselves] on the atomic level, atoms are doing tawaf and [this circular motion] creates the energy that sustains existence. For us we make tawaf of his house, we are doing the same things as the rest of creation. And [this means] that the micro level reflects the macro level.”

Worship is the raison d’être of all created beings, Allah (SWT) says,

“I did not create the jinn and mankind except to worship Me.” (Surah Adh-Dhariyat 51:56)

What an honour it is to finally realise that Allah (SWT) chose to praise himself through us, as Professor Bilal Ware wrote:

“If you are blessed to be able to intensify your worship, give thanks that God allowed you to be used as an instrument through which the divine essence has praised Itself.”

This feeling was never more powerful than when I was in front of the Kaaba. During tawaf, I was struck by a powerful juxtaposition between what I saw and felt when looking at my eye level versus when my gaze was raised just an inch above people’s heads. This prompted me to reflect on what that meant in terms of our relationship with Allah (SWT). At eye level, I was distracted by pilgrims from all walks of life, children stumbling, cleaners mopping the floor, women adjusting their hijabs and young men sending videos to their families back home. It was a cacophony of life as we have gotten accustomed to it. Whereas only an inch above was a beautiful house towering over our heads with golden threads remembering the names of Allah (SWT), and reminding us that only this matters, and that our sole duty is servitude – Ibadah.

3. Remembering that even if we speak languages unintelligible to each other, the meaning is the same

The curse of Babel keeps me up at night. As the biblical story goes, all of humanity used to speak the same language and communicate with each other perfectly. With this superpower at their disposal, they decided to build a tower high enough to reach the heavens, so as to elevate themselves above God. As punishment for this grave hubris, God confused their tongues, and they could no longer communicate with each other. I truly believe that the tragedy of man lies in this mutual unintelligibility of languages. It’s understandable why a native Chinese speaker might not be able to understand a native Russian speaker. However, it is less clear why two speakers of the same language have so much trouble communicating clearly with one another.

This is explained by sociolinguistics as the phenomenon of mismatch between the word used (signifier) and the intended meaning (signified). For example, freedom is a signifier, but the way freedom is interpreted varies (signified). This is exemplified by the futile and infuriating media debates about the genocide against our Palestinian family. The reason why hosts and guests are speaking past each other is not because they have different points of view, but because they do not share the basic assumptions upon which these debates are built. And this is a problem of definitions before politics. For example, if we fail to agree on what the signifier “human” entails, then what hope do we have for a conclusion, or peace, or even a ceasefire.

What I witnessed during tawaf, on the other hand, was a beautiful example of breaking the curse of Babel. In Islam, I learned that even if the signifier varies (different languages), the signified is the same (the Oneness and Omnipotence of Allah). Hearing du’as uttered in different languages and seeing people from all four corners of the world in the same place was nothing short of a miracle.

“People, We created you all from a single man and a single woman, and made you into races and tribes so that you should recognize one another. In God’s eyes, the most honoured of you are the ones most mindful of Him: God is all knowing, all aware.” (Surah Al-Hujurat 49:13)

I felt belonging to an ummah that cuts across race, age, language and gender, all unified by the worship of Allah. Truly “We are all God’s Metaphors” as Dr. Ali Z Hussein once wrote, we are created to reflect Allah’s Divine Attributes, and to get to know each other is to slowly get to know the Divine.

4. Remembering our purpose

There is a lot of postmodern anxiety around finding ‘our purpose in life.’ It is often assumed that our efforts are wasted if they do not contribute to a clearly defined purpose – one that fits neatly in an Instagram bio. Our relentless search for this purpose is in fact a search for meaning, without which our 9-5 grinding away becomes meaningless. Some lucky people have found their life’s purpose but for many others, it is a work in progress. Maybe because their various talents cannot be restricted to one area or maybe they refuse to monetize the thing that gives them the most joy. Maybe, just maybe, it is because their efforts are not aligned with the will of Allah (SWT) who granted them success – tawfīq – in another area of their lives.

Here, remembering “La ilaha illa Allah” was a powerful vaccine against type-A overachiever Personality Disorder (I see my fellow sisters.) ‘La ilaha illa Allah’ is not just an affirmation of Allah (SWT)’s Oneness, it is an active reordering of priorities. It subverts the illusion of control upon which hinges that balance between trust in Allah (SWT)’s plan tawakkul and laziness in our tawaakul. Laziness in our tawaakul entails a complete dependence upon Allah (SWT), unaccompanied by any effort which is understood as an extreme position. On the other hand, true tawakkul, strikes a healthy middle by striving towards our goals without attachment to the outcome and knowing that Allah (SWT) is the best of planners.

In the same way, relentlessly pursuing a ‘purpose’ as an end in itself can blind us to the possibilities Allah (SWT) has in store for us. Perhaps a better strategy would be to act in alignment with our values regardless of where it will land, not for the sake of ‘fulfilling our life’s purpose’ but for the sake of Allah (SWT). Instead of chasing a destination unknown, we make sure our starting point is the correct one. Ultimately, there will be peace in knowing that barakah is a powerful multiplier that increases the value of any action performed to please Allah (SWT).

5. Remembering that our submission to Islam is a powerful act of will.

During congregational prayer in Madinah, there is a moment of absolute silence during sujood, a powerful collective act of submission bringing our foreheads to the ground. The toddlers whose mothers have suddenly gone quiet and unresponsive, are heard crying out with such helplessness and urgency that one would think they had been abandoned for days. I smiled during my sujood thinking isn’t that what we are all doing right now? Crying out in helpless du’as wanting to be in Allah (SWT)’s proximity and to witness the manifestations of His beautiful names, Asmaa’ al-Jamal, in our lives.

We long for His healing presence (Uns أنس ) that can only be found in complete submission, and yet we are often unwilling to let go of whatever is tethering us to this earth. Letting go and embracing uncertainty is not just a twitter pop psychology trend, letting go is paradoxically rooted in an unshakable certainty that Allah (SWT) will never leave us to our own devices. He will guide us with elegant care (lutf لطف) through turbulent waters to a safe haven. ‘Musa (AS) said,

قَالَ كَلَّا ۖ إِنَّ مَعِيَ رَبِّي سَيَهْدِينِ

“No, my Lord is with me: He will guide me,’’ (Surah Ash-Shu’ara 26:62).

John O’Donohue, the late Irish Poet and Priest, writes beautifully about this longing for the divine:

“The secret immensity of the soul is the longing for the divine. […] Our longing is an echo of the divine longing for us. Our longing is the living imprint of divine desire. This desire lives in each of us in that ineffable space in the heart where nothing else can satisfy or still us. […] The glory of human presence is the divine longing fully alive.”

The fact that we are separated from divine proximity is the source of all our angst and our constant longing to belong is only a symptom of that distance. The paradox here is that we actively chase this sense of belonging through various means which almost always fall short. To illustrate this, consider that your longing to belong is a shadow that follows you around, and belonging is light dimmed by that shadow. Longing chases after belonging, desperately trying to catch up but the tragedy is that the shadow keeps eclipsing the light. Only when longing stops is when belonging to the divine can truly shine and illuminate the dark corners of our soul.

6. Remembering our destination

We all know a teenager who read Nietzsche and their personality never recovered. How ‘cool’ it is to be a nihilist, to scoff away anything that mattered with cynicism and to declare with a knowing smirk: “all I know is that I know nothing.” Few things are more irritating. During undergraduate studies, the bane of my existence was trying to figure out how Nietzsche’s nihilism and Islam’s meaningful message that I hold dear could be squared. It created some cognitive dissonance that I managed to hide from my closest friends, until one day the solution came to me during an evening walk. Our actions are saved from an inherent meaninglessness when they are preceded by a clear and sincere intention.

Setting intentions was a practice my mother instilled in us as children. ”Why was eating delicious food an act of worship?”, we asked. “Because then when you say ‘Alhamdulillah’ from the bottom of your heart, you’ll mean it”, she answered with a smile. Sheikh Musab Penfound eloquently describes this as a transmutation when he said “sincere intention is the elixir which transforms spiritual lead, which is worthless, into spiritual gold”. It turns acts that are permissible (neither good nor bad, neutral acts) into acts of worship. When we are aware of the immense potential within the most mundane tasks and states of the heart, we immediately reorient ourselves to the true destination, the akhirah.

Sheikh Musab then reminds us of an important distinction between Ikhlass al-Niyyah, the stripping away of motives, and Sidq al-Niyyah, absolute sincerity in intention. While Ikhlass asks us to carry out an action for the sake of Allah (SWT) and not for the validation by others, Sidq asks us to seek neither validation from others nor validation from our egos. Sidq al-Niyyah, is a space of constant battling Mujahada (striving) and since ego validation is elusive and insidious, it is where most of us stumble.

In the end, remembering these innate truths are necessary to reach our ultimate destination. The questions we were asked when the oath was taken, will be the same as the ones we will be asked on the Day of Judgement – a confirmation of Allah (SWT)’s divinity (Rububiyyah) and of our servanthood (‘ubudiyyah).

According to Sufi jurist and scholar, Ibn Ata Allah Al-Iskandari, there are two kinds of servanthood, that of appointment or stewardship (takleef) and that of enlightenment (ta’reef). He gives the example of Prophet Adam (AS) when he was sent down from Heaven and explains that it is understood not as a punishment but as an opportunity to be awarded both kinds of servanthood. First, Allah said,

“I am putting a successor on earth” (Surah Al-Baqarah 2:30)

Adam (AS) took up his role as a steward fulfilling servanthood of appointment. And with that he was graced with servanthood of enlightenment since it was an opportunity to know some of Allah (SWT)’s divine names whose meanings were not clear in Jannah. If in Jannah, Prophet Adam (AS) knew the names of Al-Qadīr, al-Murīd through Allah (SWT)’s generosity, now he will come to know Al-Tawwab, Al Wadud and Ar-Rahim through Allah (SWT)’s Might and Forgiveness. This understanding of Prophet Adam’s (AS) journey offers us courage and solace in knowing that any blessing that we are graced with or any trial that afflicts us is ultimately a way of knowing Allah better and elevating our status of servanthood.

References:

Eternal Echoes: Celtic Reflections on Our Yearning to Belong by John O’Donohue

Soul’s compass lecture series by Sheikh Musab Pendound on Spotify

Illuminating Guidance on the Dropping of Self-Direction by Shaykh Ibn ‘Ata’illah as-Sakandari

Alaa Badr

Lulu is an Egyptian researcher based in Florence, Italy. She is interested in contemporary intellectual history and new modes of knowledge production in the MENA region, as a part of her PhD project at the European University Institute. She holds a BA & an MA from SciencesPo Paris in Political Science. She is fascinated by languages and language games and worries that the curse of babel is getting worse. You can find her on Instagram: @Lulu__Badr