The Things They Have Seen: The Plight of the Kuwaiti Bedoon

by Hiba Noor Khan in Culture & Lifestyle on 11th December, 2018

The first time I came across the Kuwaiti Bedoon population was through my job as a Refugee Advocacy Worker. As someone who has been an activist and campaigner for human rights causes globally, for as long as I can remember, it came as a big shock to me just how little this group of horrifically oppressed humans are spoken of.

The problem…

There are more than 100,000 stateless Bedoon people currently residing in an oil-rich haven of Kuwait, many of them belonging to families who have been there for generations upon generations. Despite this, the majority of this demographic face reduced, or at times diminished access to employment, education, healthcare provision and state support, and when they protested this, they would face violence, torture, and imprisonment.

The word Bedoon is short for Bedoon Jinsiya, an Arabic phrase meaning ‘without nationality’. They are a stateless minority, who at the time of Kuwait’s independence were not included as citizens. This issue of statelessness in the Gulf is not by any means limited to Kuwait, with an estimated 500,000 reported to be living across the entire region.

The government refuses to recognise them as Kuwaiti, continuing to categorise them as illegal residents (claiming they are Iraqi and Saudi immigrants), despite the fact that many of them have no links to any other country whatsoever. This refusal of status results in the majority of the Bedoon population living in abject poverty, fortunate if they find work in the informal sector.

Related

This Week in World News: Starting with Rohingya & Iran

Because We’re Worth It: What Does Representation Really Mean?

The Kanga Project: Gifting The Women of Rural Zanzibar

Roots…

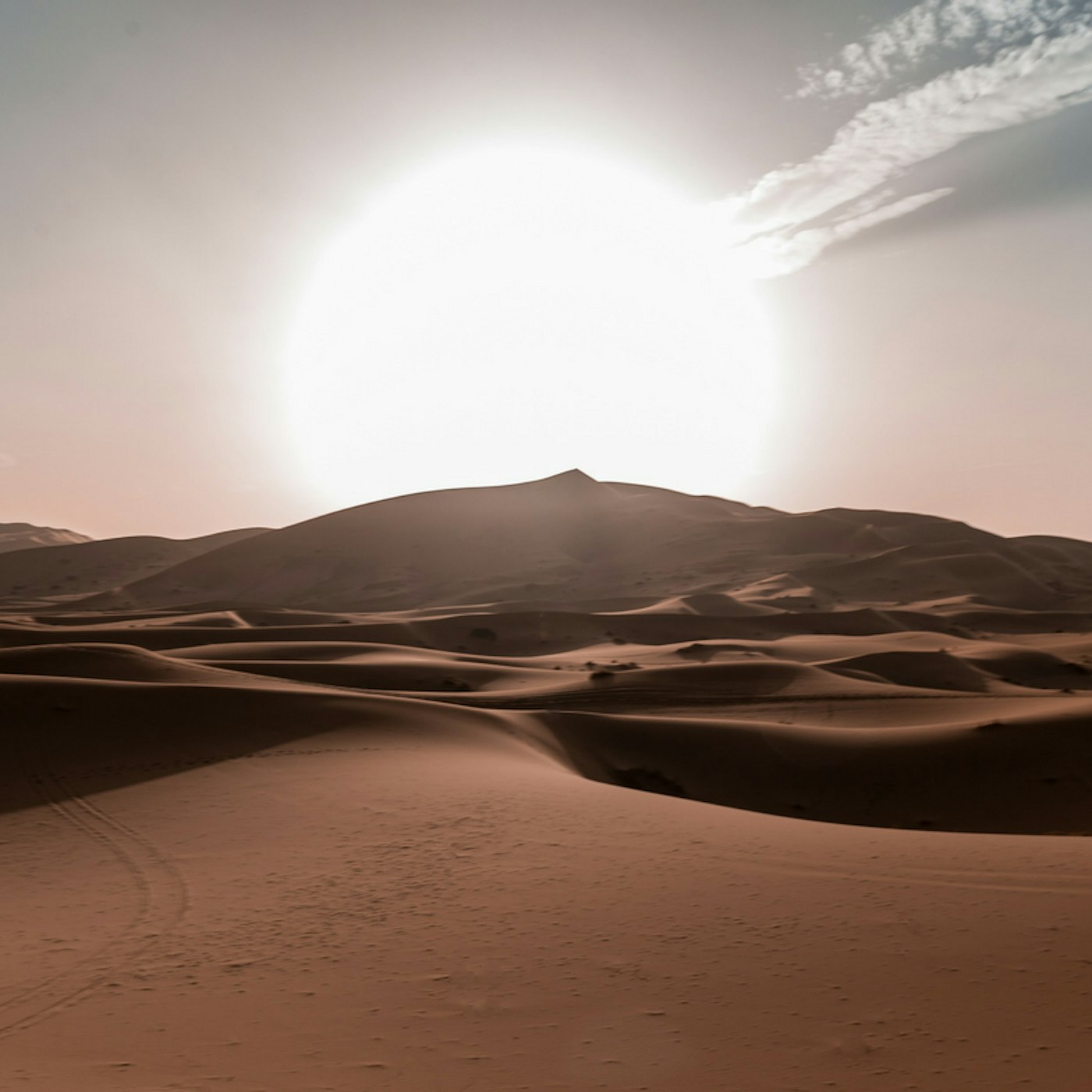

The vast majority of the Bedoon originate from nomadic tribes from around the Arabian Peninsula who were living in the country in 1961, many were refused the right to register as a citizen. The law that now represses them in every aspect of their lives undeniably favoured the people who were living in cities, or who were fortunate enough to have connections to affluent families. The traditional tribal system that existed throughout the region for as long as the books go back was disrupted, and whether it was as a result of lack of awareness of the necessity to do so, lack of documentation linking them to the land, or simply illiteracy, these tribal communities did not register for citizenship.

It is estimated that as much as a third of the entire population of Kuwait at that time did not gain citizenship, which was an entirely foreign concept considering the migratory nature of native Arabian tribes.

For the first few decades after independence from the British, the distinction between those with Kuwaiti citizenship and those without, held relatively minor visible implications, the main one being that those without were not able to vote, but were given free healthcare: were able to register marriages, and hold documentation. Following the Iraq Iran war and Iranian revolution in the 80s, the Kuwaiti government began to feel more and more vulnerable and began to view the Bedoon as a national security threat. It was believed that some Iraqis, alongside refugees, were arriving into the country and posing as Bedoon after disposing of their papers in order to avoid military service/persecution in their home country. In 1986 the status of Bedoon in Kuwait was officially changed to ‘illegal.’ Experiencing a series of human rights violations, fired en masse from jobs, excluded from education, housing, and healthcare provision, as well as forcible expulsion.

Conditions Worsened…

Following the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq, and the Gulf War that ensued, the position of the Bedoon became even more difficult and hostile, after being scapegoated and stigmatised through political-military disputes.

Many were abused in detention centres, and around 10,000 deported. Since then, various token gestures have been made by the government, ultimately not doing much at all to solve the issue of compromised human rights abuses.

The restrictive nationality laws echoing throughout the Gulf meant that all children born to Bedoon parents were also deemed Bedoon. Bedoon girls and women report regular institutional sexual harassment, often coming from government officials exploiting their vulnerability as a marginalized community.

After a surge in protests taking place around the time of the Arab Spring, the use of tear gas, smoke bombs, and water cannons were utilised to keep the protestors at bay, before many of those arrested and detained reported beatings, torture, and sexual abuse. Following this, hundreds of the Bedoon population, who were able to leave Kuwait using forged travel documents, carried their scars and trauma across Iraq, Turkey, and into Europe. Majority of which, ended up stuck in the ‘Jungle’ in Calais. The intention to reach the UK was particularly because they believed England, the former coloniser of Kuwait would understand their plight and as a result, empathise with them, after having previously granted asylum to Bedoons.

Heartbreakingly, and very much contrary to their hopes, they found themselves trapped and victim to the violence and difficulty once again. Children of the Earth, just like the rest of us, rejected by the lines we mark the soil with.

Hiba Noor Khan

Hiba Noor Khan is a children’s author, her books include The Little War Cat, Inspiring Inventors and One Home. She has two titles to be published in 2023, including her first novel – Safiyyah’s War. Her books have been listed for national awards and translated into Swedish, Korean, Turkish, Breton and counting. She secretly wants to be an explorer, and is happiest surrounded by nature, especially near the ocean.