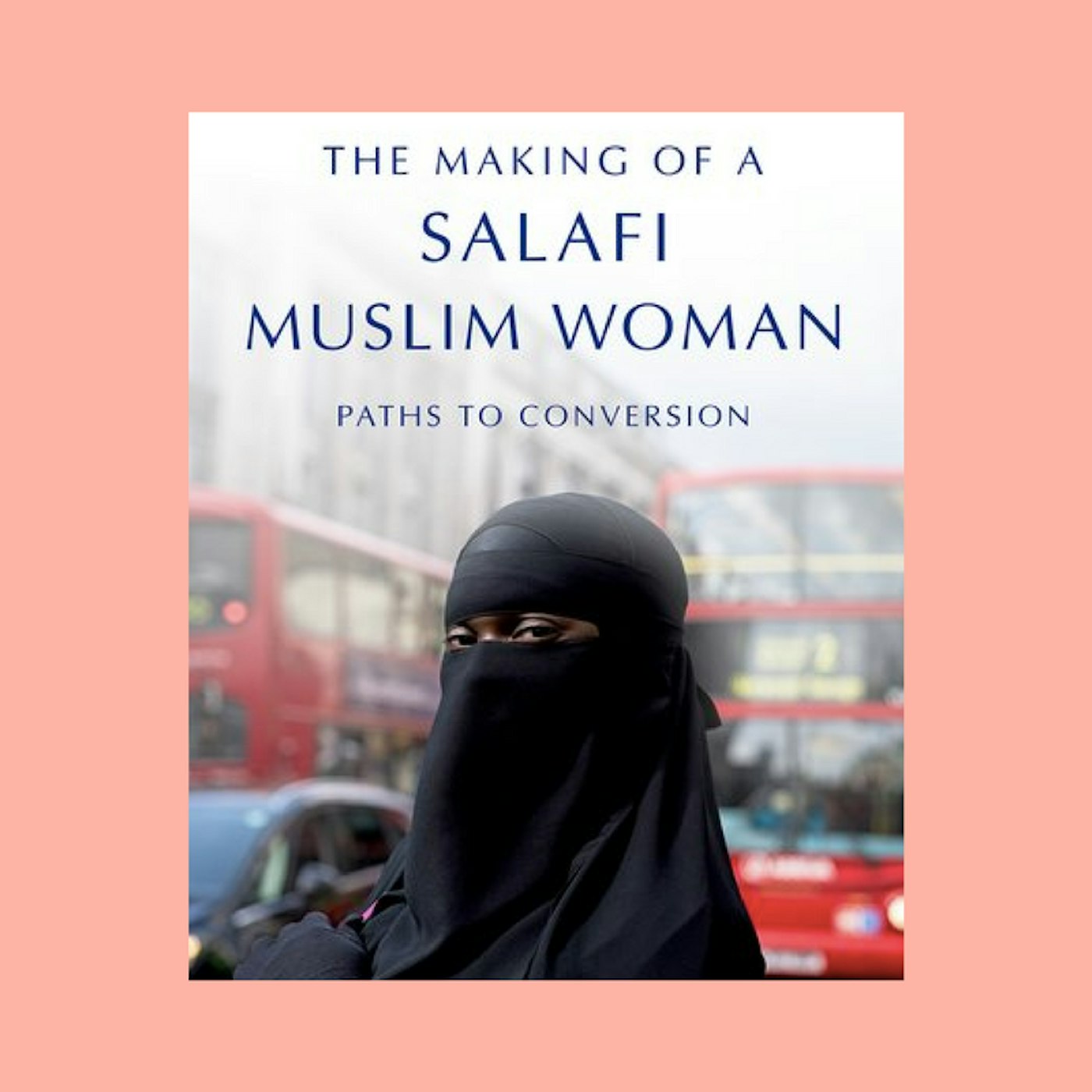

Book Review: The Making of a Salafi Muslim Woman – Paths to Conversion by the Salafi Feminist

by Zainab bint Younus in Culture & Lifestyle on 12th March, 2018

“The Making of a Salafi Muslim Woman” by Dr. Anabel Inge began as a thesis and ended up as a fully-fledged book. This book is unique in that it takes a long, detailed look at the daily reality of Salafi Muslim women in the UK, not from the informal perspective of a Muslim experiencing complicated intra-community politics, but as a non-Muslim woman included in the private confidences of the women whose stories are being told.

The Intention

Dr. Inge’s approach is refreshing, not least because she does not seek to push forth a particular agenda or perpetuate a deliberately negative image of the Salafi community (which does enough to give itself a bad reputation). Rather, as she states in the very beginning of her book: “I assumed that… Salafi women have agency and power over their lives like anybody else.”

Reading this book as a self-identifying Salafi woman, this statement gave me the reassurance that the stories of the women would not be twisted and used to suit a certain agenda or to fear-monger. Instead, there was a sense of genuine sincerity regarding the author’s choice to study this particular demographic.

The Introduction lays the foundation for all readers – Muslim and non-Muslim alike – to understand the context of discussing Salafiyyah as both an ideological movement and a Muslim sub-culture of sorts operating within a post 9/11 political environment.

There is a clear distinguishing between Salafiyyah and those whom they are often lumped with, such as Al-Qaeda, ISIS, and other Khawaarij groups that many feel no hesitancy in conflating with one another. I greatly appreciated the author’s discussion on how she gathered the material for her book and the challenge of being a researcher on a specialized topic with a community that is rightly suspicious and protective of their spaces. I always find it interesting when “outsiders” share their observations/experiences with our communities – how they view our quirks and habits.

First Chapter

The first chapter of the book acts as a mini history lesson in the development and rise of Salafiyyah in the UK. As a Muslim reader from Canada, where Salafiyyah’s history and current existence is far different from that of our cousins in the UK, I found this particularly interesting. It is rare to find a semi-academic account of inter-Muslim-community histories, which we as Muslims tend to neglect in our pursuit of trying to keep up with the present. While Umar Lee’s “Rise and Fall of the Salafi Da’wah” article series was an enlightening insider view of the history of the Salafi movement in North America, there has been little other material available that discusses the community history of Salafiyyah elsewhere.

The segment on the ethnic demographics of Salafiyyah in the UK revealed some unexpected tidbits of information – educated young Somali women make up a significant portion of the UK’s female Salafi community; other British-Afro ethnicities contribute to the overall Salafi population as well, particularly converts.

While the book is, primarily, a work of academic research, Dr. Inge does not fall into dry technicalities at the expense of the humanity of those whom she speaks about. Indeed, I was quite amused when she documented her first exposure to Muslims using the phrase “InshaAllah” as a polite way of saying “no,” and women canceling plans because “my husband said so” (which, as we all know, is the most convenient excuse a Muslim woman can have, even and especially when the husband has no involvement whatsoever in that decision). I laughed out loud when she recounted her first co-wife proposal of marriage… from someone who initially suspected her of being an agent for MI5.

The Next Chapters

The book progresses by introducing us to the women whom Dr. Inge interacted with over a lengthy period of time, learning about each individual’s personal journey to Islam (and subsequently, Salafiyyah) – their backgrounds, their childhoods, the cultural context in which they became attracted to the Salafi da’wah, navigating the political environment of Britain as visibly Muslim women, pursuing marriage, and more. I found it fascinating that “being Muslim” (or at least looking the part) was an actual trend in certain areas. That certain London gangsters were trying to use Islam as some kind of branding made me want to read some Muslim urban fiction. On a serious note, it was interesting to learn what factors led many women to choose Salafiyyah in spite of its own bad reputation: Akhlaaq (good character), knowledge of Deen, and persistence in da’wah without fixating on Salafiyyah’s labels or PDF reputations or other cliched silliness.

What it Means to Me

It isn’t rocket science – it’s the basic principles of da’wah, the Sunnah of Rasulullah himself – but it was an excellent reminder that those of us who would purport to be Salafi should be keeping in mind and which, unfortunately, many do not – and then bitterly wonder why folks would rather go join other groups instead. Ukhuwwah is a vital ingredient of da’wah, and not in a clique-ish, cult-ish manner.

For some of the women who shared their stories, it made all the difference to be welcomed by fellow Muslims who didn’t look down at them for their pasts. Piercings or pregnancies out of wedlock, so long as one was choosing to return to the Deen, there was no issue.

The most important part of these women’s choice to turn to Salafiyyah, however, was an intellectual conviction. And that is what I also identify with: the clear, fitrah-centric approach to Tawheed and emaan. Kitab at-Tawheed aside, it is the basic facts about Tawheed that are most reassuring; the freedom from depending on wazifas and peer saabs and worrying that one’s relationship with Allah isn’t good enough to count, or to matter. What I felt that Dr. Inge’s book did most for was to give me a greater appreciation for what and how Salafiyyah comes off as to an outside, objective observer who doesn’t share our emotional baggage. Whether it’s things like trying a little too hard to be “Salafi enough” – particularly with regards to outward markers – to the emphasis on Tawheed and purifying oneself of bid’ah, it’s refreshing to recognize those aspects of ourselves that are both praiseworthy and otherwise.

I deeply appreciated the recognition that for many Salafi women, the pull to Salafiyyah was/ is very much both an intellectual and spiritual journey. It reminded me that while the culture of Salafiyyah can often be obnoxious and unreasonable, there is something deeper that does call to and attract those who search for something deeper – for those who genuinely want the Haqq, who look for something more.

Particularly poignant was the chapter highlighting the practical inconsistencies of Salafi socio-religious standards/ expectations for women. Seeking knowledge is Fardh ‘ayn, but the ever-present insistence on a woman’s domestic duties presents a challenge that Muslim women still face – especially when it is drummed into our heads that even preparing a husband’s meal is Waajib and more of a priority than anything else. What this book highlighted, and what I thought was so important about it, is that it focused on the lived experiences of Salafi women… which are very, very different from those of Salafi men.

Whether in terms of the culture of the community, or how Islam is taught and internalized, to the challenges of finding a spouse and contending with things not working out, to struggling with both family tensions and challenges in the academic world/ workforce… what women go through is so, so different, and so often ignored and underappreciated. This book was extremely well-written, thoughtful, well-researched. To me, being completely unfamiliar with Salafiyyah in the UK, it was a fascinating insight into how the culture of Salafiyyah is both same and different in various geographical regions.

Stamp of Approval

Obviously, the book is not exhaustive of *all* aspects of being a Salafi woman, nor does it necessarily touch on how the culture of Salafiyyah has evolved, especially recently.Nonetheless, I highly recommend it. UK readers will probably understand certain nuances better or identify possible inaccuracies, but overall I very much enjoyed the research shared and feel that it is a valuable first insight for those who might never have considered learning about Salafiyyah outside of a cliche Muslim-men-and-politics-and-oppressed-veiled-women perspective.

Zainab bint Younus

Zainab bint Younus is a Canadian Muslim woman who writes on Muslim women's issues, gender related injustice in the Muslim community, and Muslim women in Islamic history. She has taken a social media sabbatical but can still be found on Instagram (@bintyounus) and at her blog: https://phoenixfaithandfire.blogspot.com/ IG: @bintyounus