ECHOES: An Exploration on Memory, Language and Family Archives

by Sana Ginwalla in Culture & Lifestyle on 30th July, 2021

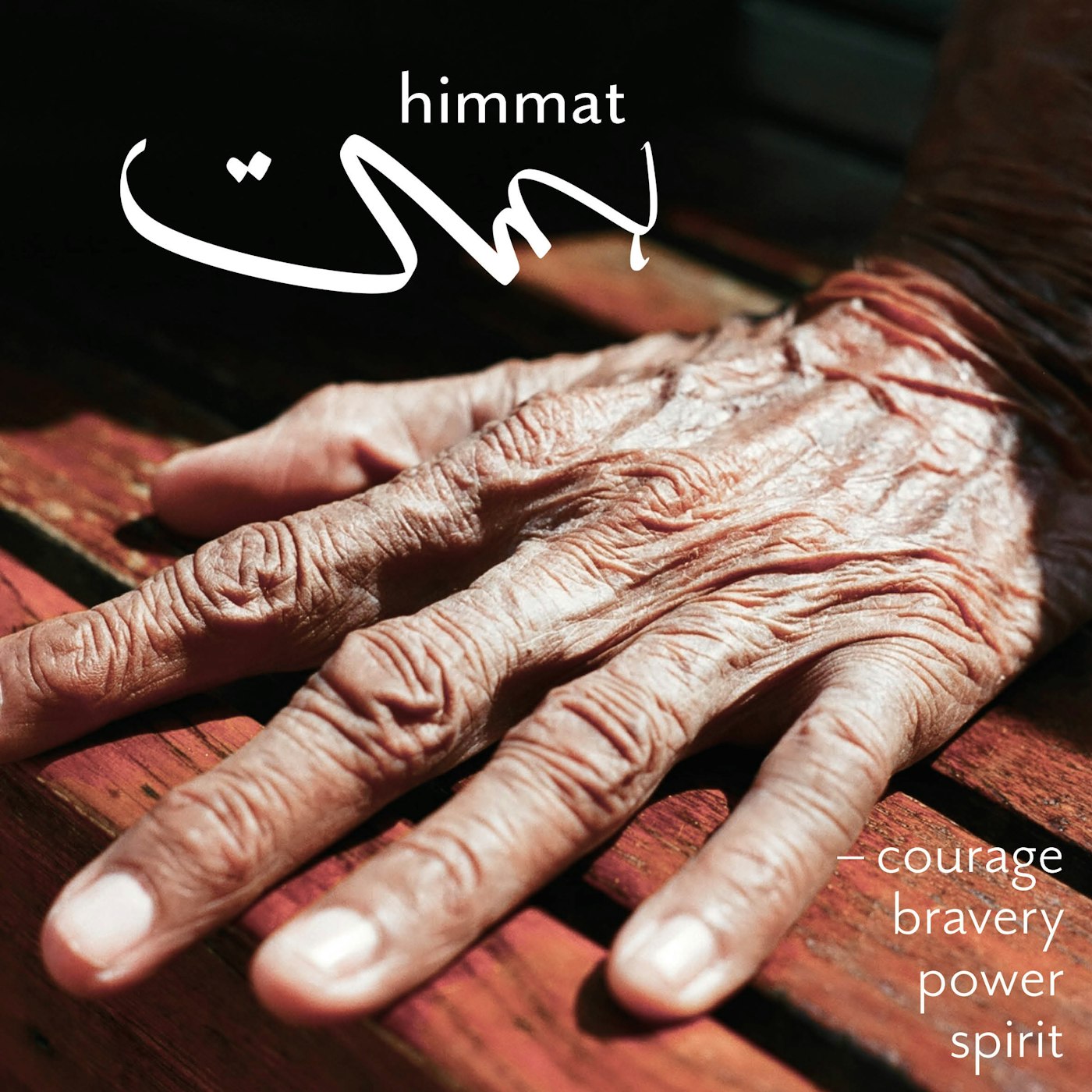

“Himmat rakho” (have courage): this was the affirmative statement that my beloved Baaji (grandfather) would say whenever we would speak in times of difficulty. Sometimes it would be used as a parting word of advice before saying goodbye on the phone, or met with a gentle yet playful pat on our head during our visits to India. Other times he would get into his usual dialogue that often felt like it started in the middle of a story, where he’d put his hand in a fist and encourage us – his English-speaking grandchildren of the Indian diaspora who could hardly speak his mother tongues of Urdu and Gujarati – to always work hard and keep busy: “kaam hodo, kaam karo. Himmat rakho.” (Look for work, work hard, have courage).

In July 2020, my father tested positive for Covid, so he, my mum and I were in quarantine together for 6 weeks in our home in Lusaka, Zambia. My Baaji, (who was still alive then but passed from Covid only two months later), would call from India and impart his best advice every time: “Himmat rakho”.

As the weeks of quarantine went by, Himmat became the word that constantly echoed in several phone conversations with concerned family members around the world. Other words such as “taaqat” (strength) or “bharosa“ (trust/faith) would reverberate through the passage of our house, encouraging my father on his weak days to have patience, and trust in God – “Sabr karo aur Allah pe bharosa rakho”. I started to notice how the language in the house began to change according the circumstance we were in. Words relating to health, strength and faith resounded repeatedly, and I became hyper-observant of the other words in Urdu that were used in my parents’ conversations.

My Urdu knowledge had developed mostly in a conversational and domestic environment, and though my parents speak Urdu in the home, I’ve always replied to both my parents in English.

This changed during our long quarantine together, as I found myself speaking Urdu a little more, building my practice and confidence around it. By engaging in this linguistic journey, I began to listen more attentively to the words that resonated in our household to reflect on what they actually meant. As I observed the repeated exchange of certain words at home, I began asking, researching, and writing them down; developing a personal dictionary of sorts.

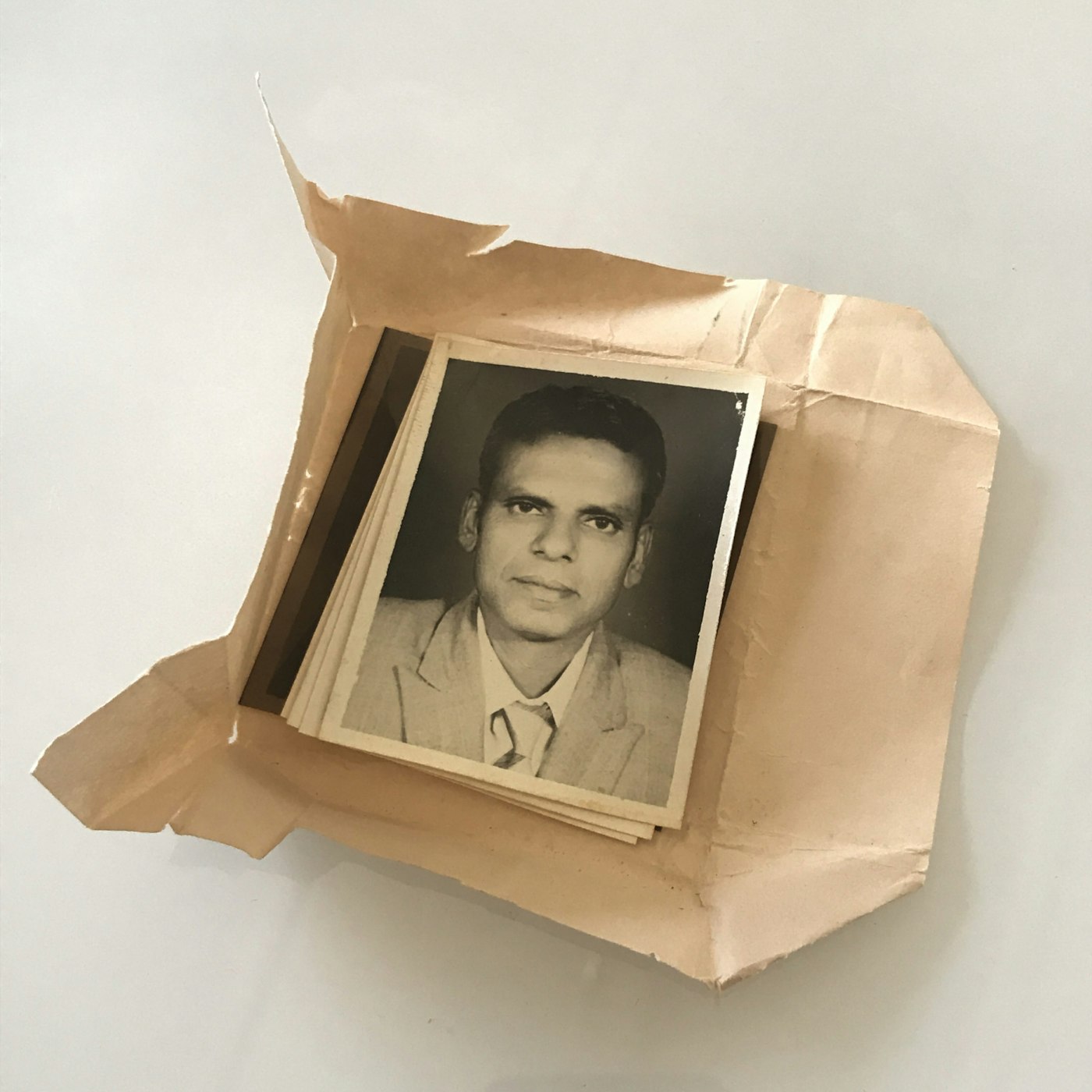

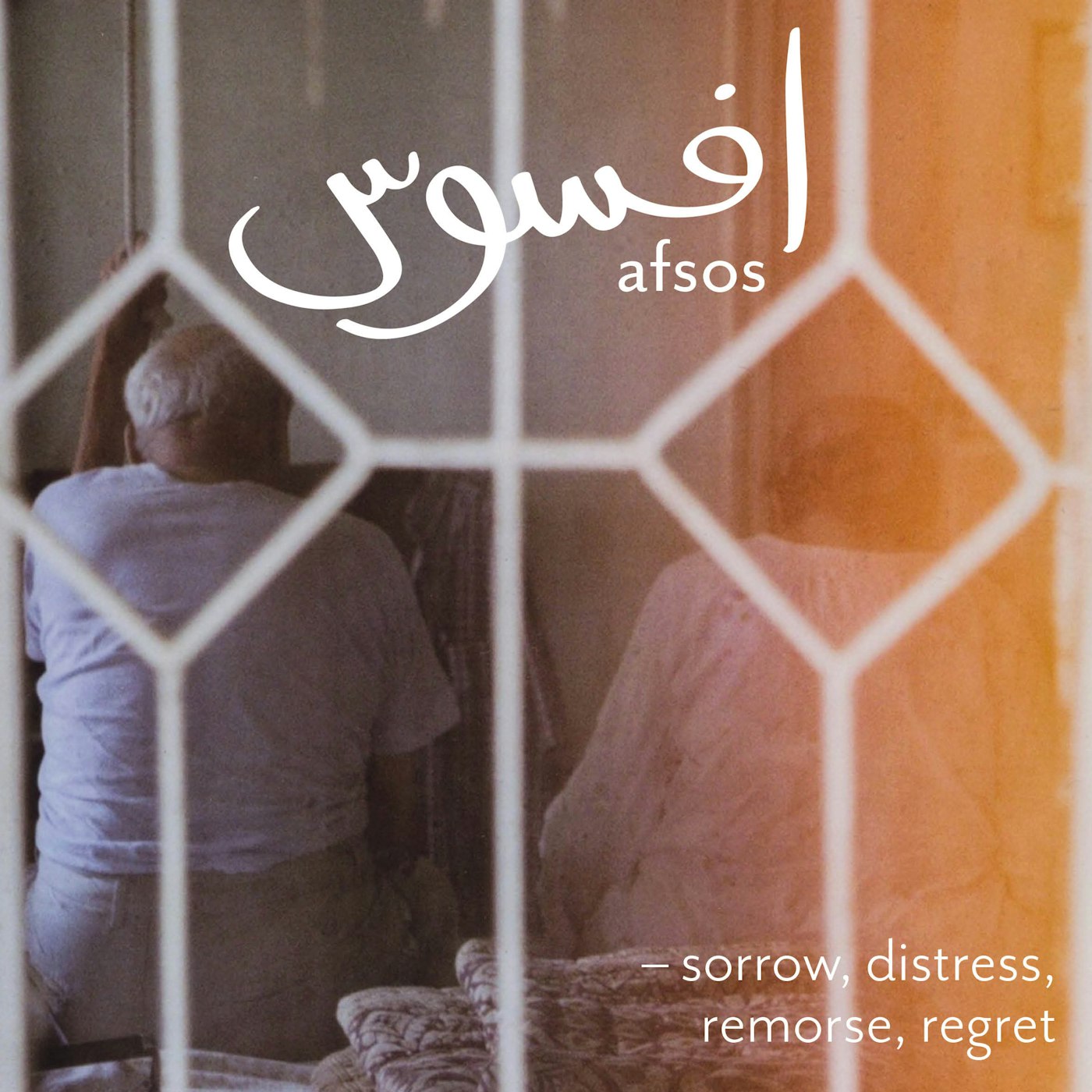

It just so happened that as my father recovered from COVID, his father contracted it in India only a few days later, and the same words that were used to encourage my dad, were yet again echoed in phone conversations with my Baaji. The very word we associated with him and his character, were used by his children and grandchildren – affirming him to have sabr, himmat, and bharosa in God. As I came to accept the reality of the situation with my Baaji’s health I realised that I soon will only be left with memories of him. As I navigated this afsos (sorrow, grief) and mentally prepared for what was to come, the words that I gathered started to mean something more to me emotionally. These words, like photographs, evoked a sense of connection to my ancestry and those who have lived before me. Having consistently made and worked with photographs of my grandparents for almost 6 years, my identity politics and sense of belonging, heritage, family and “Indianness” was a familiar trope I explored in my personal artistic practices. I had previously engaged in photography, film, collage, writing and design publications as a means to challenge the possibilities and limitations of memory – continually finding ways to converse with my sense of self in the visual languages I knew best.

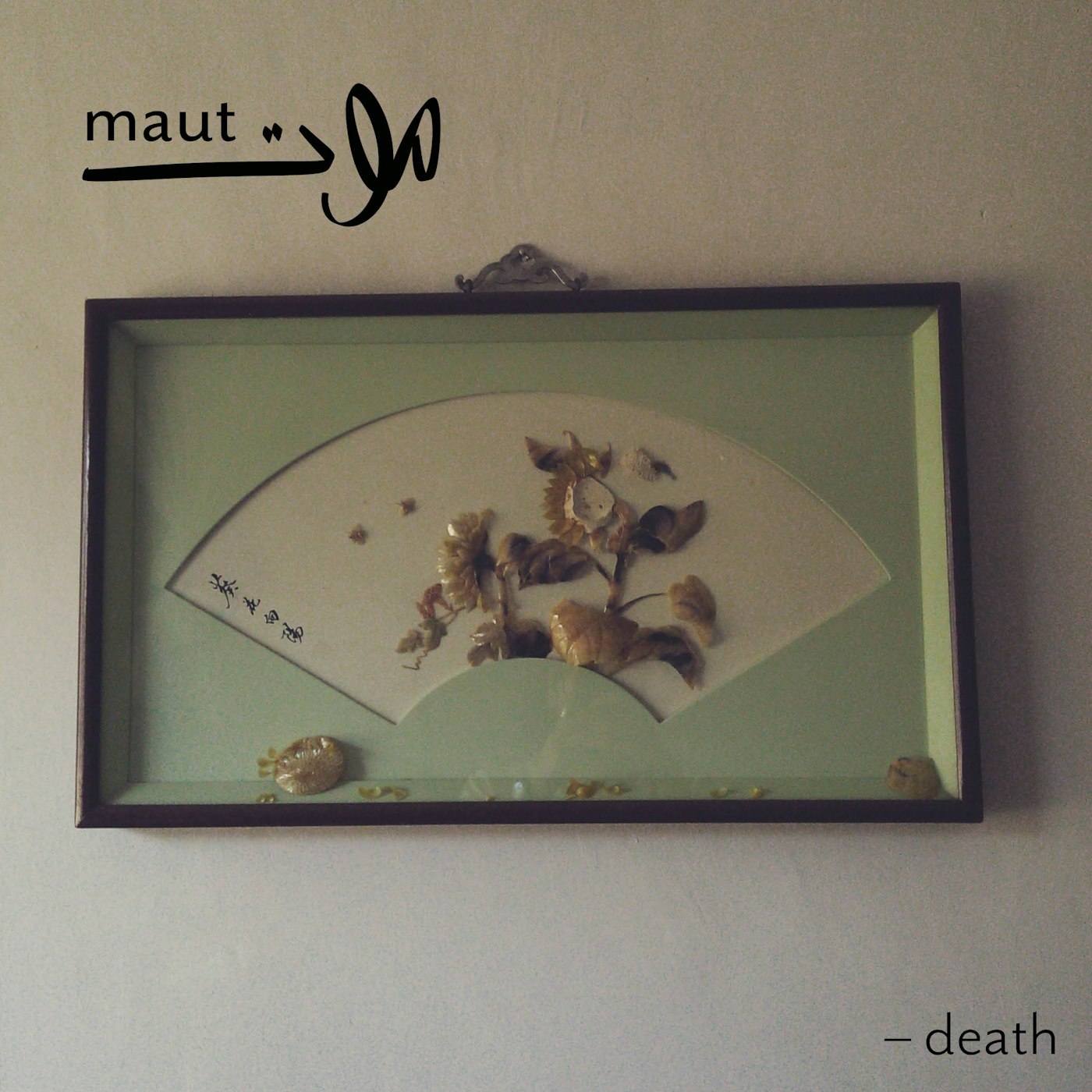

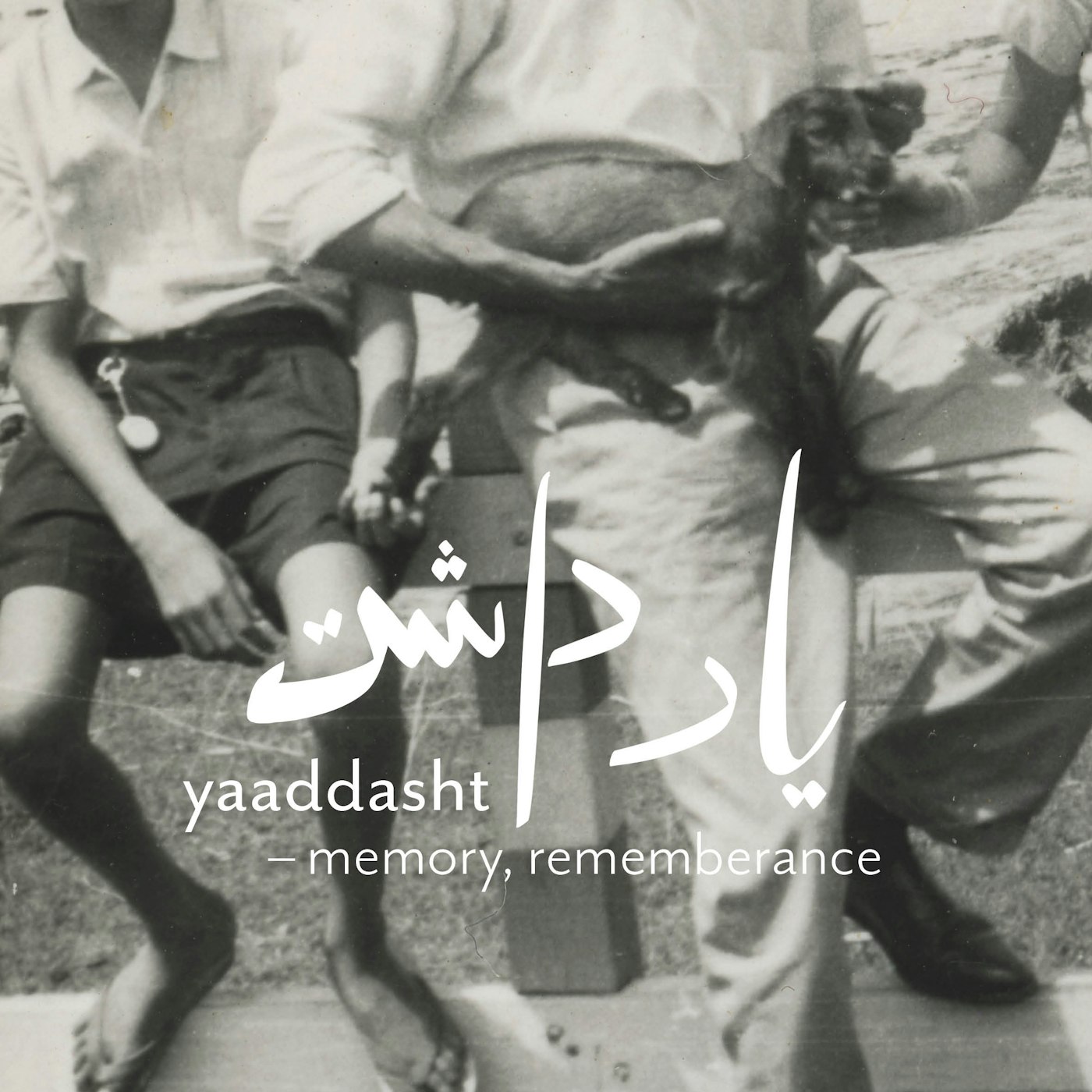

As the family experienced a distressing period with my Baaji’s death and several other key elders in the family in the following months, my grieving process fed into my journey with Urdu – evolving it into a project that sought to look back in order to look forward, to echo the past into the present. To preserve memory, honour our forefathers and facilitate a different way to engage in remembering altogether. I had spent a lot of time during 2020 collecting and scanning negatives and prints from our family archives, and I began to wonder how some of those images could work as labels for the words from the personal Urdu dictionary that I had started building. I mined for more images that related to the emotions around the project, and worked towards another mode of curation, creation and communication entirely. By using a non-visual language I was not fluent in, I allowed one part of my self (the visual artist) to echo with the other (the observant linguist in quarantine).

Echoes thus manifested as a visual sound wave, one that exercised memory in a way that included my family members too – asking them to add words to the list, while my sister hand-lettered the Urdu words to reflect their mood. By using nuanced images from our family archives to label the words, Echoes is a curated visual dictionary of Urdu words that have echoed through homes and generations in my family; in the hopes that our generation could continue to do so with next. This project therefore exists to preserve knowledge and continue to actively build on it for the family’s generations to come.

Echoes is part of a collection of projects called Yaaddasht by Sana Ginwalla which is where all my mixed media experimentations around memory, language and family archives reside.

Sana Ginwalla

Sana Ginwalla – photographer, curator, archivist sanaginwalla.com Interested in politics of identity, home and belonging, Sana Ginwalla is a Zambia-born photographer, curator and writer. She is the founder of Everyday Lusaka and Zambia Belonging – platforms that focus on shifting the lens and showcasing the overlooked and relatable everyday moments of the past and present. Urdu lettering by Zabeen Ginwalla (@bypaperface) Digital artworks by Sana Ginwalla (@sana.ononas) Photographs from the Ginwalla Family Archive. The archive can be found here IG: @yaad_dasht